Slop Capitalism, AI Ghibli, and Risotto alla Milanese

The only life worth living is the real one.

By now, you’ve heard about the latest AI nonsense: the ability to ape the style of Studio Ghibli. Upload a photo and the machine spits you back a version of it rendered with flat shading and thin outlines. it doesn’t cost money, it barely costs time, and you’ll never be able to divine the precise impact of the specific data you provided it. So why not “Ghiblify” all your photos?

Adam Aleksic of The Etymology Nerd recently wrote a couple of great articles (1, 2) on AI-generated images (I won’t call them art - language is power) and their contribution to“slop capitalism”.

The phrase “slop capitalism” is certainly evocative, and you probably have a visceral sense of what it means. Here, I’m using it to mean media — images, text, video, audio, etc. — with no attention or purpose driving it other than a desire to earn money, primarily by capturing attention.

Aleksic cites meme researcher Aidan Walker’s assertion that a primary goal of AI generation and slop capitalism is to “crowd out actual human voices on platforms”. Slop doesn’t necessarily have to be AI-created. I certainly wrote my fair share of it when I was writing garbage articles for content mills at the start of my professional writing career. At this point, though, it’s cheaper to create slop in AI programs than it is to pay a writer a penny per word to write. When the incentive is profit over point of view, cheap wins, and human voices are crowded out.

Even for a regular person, who only wants to use art to enrich their own life, it’s cheaper to spit out an AI-generated image than it is to pay one of the millions of illustrators on the internet who would love to take their commission. We’re all infected with this notion that less expensive means better, because having money means having more. More what? More money. More opportunities to buy more cheap stuff.

The choice of OpenAI to release a Studio Ghibli image generator wasn’t an accident. They didn’t go after Disney, which has its own distinctive animation styles. No, they went after Studio Ghibli, where director Hayao Miyazaki is outspoken against his opposition to AI technology. “I would never wish to incorporate this technology into my work,” he told a group of programmers who demoed an AI animation for him. “I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.”

I wish I had saved the post when I first saw it (please feel free to send it to me and I will add attribution), but I scrolled past a thread arguing that the choice to create a Studio Ghibli image generator and release it to billions of people for the cost of literally no dollars at all was a show of dominance. The author argued that, in choosing to create a plagiarism machine targeting a studio that creates films about humans’ vicious relationships to each other and the environment (and the ways we have to live with the consequences of those vicious relationships), Sam Altman and OpenAI say to artists: We don’t care what you want. We can do whatever we want, and you can’t stop us.

It’s abusive behavior: I can hurt you, and you can’t stop me.

—

I think the person who argues this is a show of dominance has it partially right. But I think there’s something else going on, deeper than the desire to claim dominance. Something — dare I say — fundamentally human. A fear.

I think that underlying the desire to spend so much time and effort creating algorithms that can, with increasing superficial success, copy the output of particular people or groups, is a fear of death.

I think Sam Altman and all the other tech bros out there are afraid of dying.

—

Hayao Miyazaki is 84 years old. Soon enough he will die. Then, there will be no more Studio Ghibli movies with his personal touch.

Our time on this earth is finite. Our work is finite.

This may scare you. This may make you very sad.

It doesn’t make it not true.

—

AI image generators allow us to pretend that death is not real. If you don’t look closely, an image with the characteristic cozy color palette, flat shading, and thin outlines passes as a “Ghibli image.” If you study the image, you’ll find something wrong—lines that don’t quite make sense, or colors that don’t match in as well as they should—but if you don’t, are you going to be able to tell? Maybe not. So Miyazaki lives on, never mind that it’s in slop.

At the risk of sounding like a stoic sigma grindset TikToker, we must face death. If we are to live, we have to acknowledge that we are going to die. This is not an if, but a when.

Life is meaningful because we never know how much more of it there is. Art is valuable because one person can only create so much. Art is art because of the intention behind it, because of the person’s conscious desire to create something out of their own experience. An artist, or a group of artists, controls the final outcome. They make decisions along the way. Each decision opens some pathways and closes off others. Everything is intentional.

Accidents, like spilling the bottle of ink, open up new pathways too. The artist can accept the outcome and change the direction of work to incorporate the spill, or reject it and start over. Either way, the artist chooses with intention which pathway will best convey the message they are trying to communicate.

AI can’t do that.

—

I’m going to die.

You’re going to die.

Your parents are going to die. Your favorite barista is going to die. The fluffy dog who walks past your house every morning as you’re making coffee is going to die, sooner than you expect.

It will hurt. It’s okay. It should be this way. It’s what makes life — life.

And one thing we can do to celebrate this breathing life we have, right now, is spend some time feeding ourselves, helping our bodies continue living.

It’s risotto time. I love you.

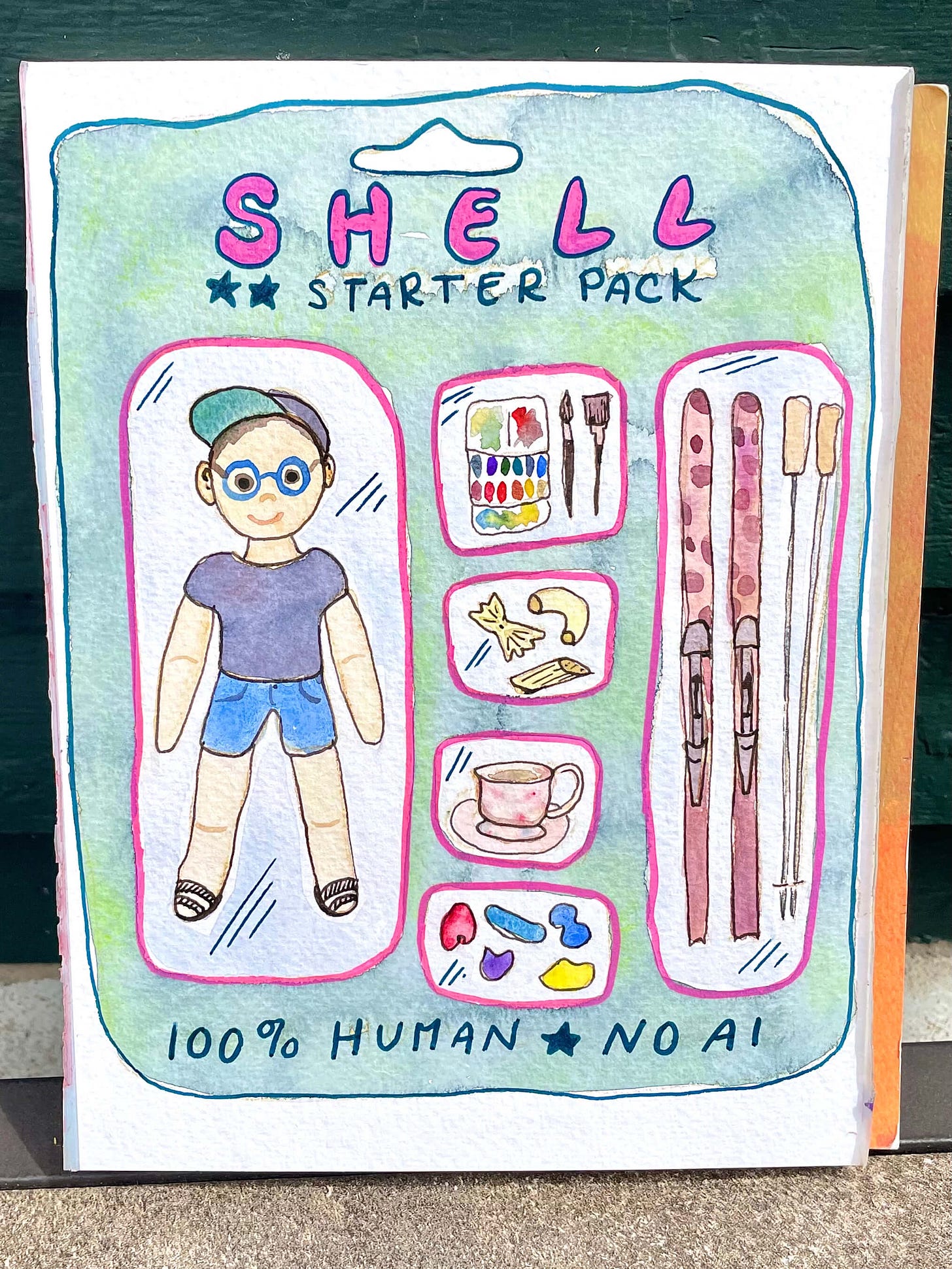

Shell

BOOK REC:

The Chaos Machine: The Inside Story of How Social Media Rewired Our Minds and Our World by Max Fisher

This is one of the best books I’ve read in a long time. Max Fisher does a deep dive into Internet history, from looking at the philosophies of the early tech bros who worked in Silicon Valley before it ever earned that name to dissecting the major Internet scandals that shape our journey down the information superhighway. Throughout, he shows the ways in which algorithms divide us rather than bring us together despite their creators’ claims to the contrary. His writing style is engaging and I looked forward to picking up the book each day.

RISOTTO ALLA MILANESE

Risotto alla Milanese is a traditional, saffron-flavored risotto. It’s delicious on its own, but its flavor is mild enough that it also forms a decadent base for risotto al salto (fried risotto pancake) and arancini (fried, cheese-stuffed risotto balls)

This recipe makes a bigger quantity than usual because I’m highly recommending you make this and save at least half—if not 90% of it—for future risotto adventures. You don’t really save time making a smaller quantity, since the rice takes about the same amount of time to cook no matter what you’ve got going on, so you may as well make extra.

I split it in half, stored one in the fridge and one in the freezer, and got two delicious nights of fried risotto out of it (plus a chef’s dinner the day I cooked it). I’ll be getting into those recipes in future RTs.

Serves 8, or 4 twice.

Ingredients:

1 tbsp vegetable bouillon paste

2 tbsp olive oil

1 onion, minced

2 cups risotto rice

1 cup dry white wine

2 pinches saffron

2 tbsp butter

1/2 c freshly grated parmesan cheese

Method:

Fill a small saucepan with water and add the bouillon paste. Bring to a boil, then reduce to a simmer. Keep warm.

In a Dutch oven, heat the olive oil over medium heat. Add the minced onion and cook, stirring frequently, until onion is translucent and tender. If the onion begins to burn, add a half cup of water to the pot.

When onion is tender and any water you added is evaporated, add the rice. Whisk until it becomes translucent around the edges. Add the wine and whisk until it is absorbed. It should happen very quickly.

Add the saffron and about 1/2 cup of stock. Whisk vigorously until absorbed. Continue adding broth, about 1/2 cup at a time, waiting until each addition is almost entirely absorbed before adding the next. As long as you stir vigorously for 10-15 seconds each time you add the broth, you don’t have to stir continuously. Risotto is very forgiving.

When the rice is tender but not mushy, turn the heat as low as it will go. Add the butter and parmesan. Stir to incorporate, then take off the heat. Taste and add salt if necessary.

Serve immediately, OR - split in half and portion into storage containers. Let cool, then store in fridge (if you’ll fry it this week) and/or freezer (for longer storage).

YEESSS, Shell!!!! I want to shout your essay from the rooftops!!!!!